Some Mechanisms of Traumatic Brain Injuries in Nebraska

Diffuse Axonal Injury

The brain is somewhat like Jell-O in a bowl. It is a soft substance with the consistency of custard and composed of millions of nerve cells that are interconnected or wired together by nerve fibers that run throughout the brain. The hard bony skull contains the brain and protects it from direct penetrating blows.

Unfortunately, the skull cannot protect the brain from the energy of such blows. When the head is struck suddenly, strikes a stationary object, is shaken suddenly, or is set in motion by sudden acceleration or deceleration forces (such as in a car wreck), energy is transmitted to the brain, and the brain moves. Because different parts of the brain have different densities, some parts of the brain move faster than other parts. When a nerve fiber runs through areas of the brain that are of different densities, different parts of that fiber also end up moving at different speeds. As a result, the fiber twists, stretches, and may even tear. This process is very similar to what happens when you shake Jell-O that is in a bowl. Just as the shaking action causes parts of the Jell-O to pull away from each other, the energy applied to the brain causes it to bounce and swirl around within the skull causing widespread trauma. The nerves no longer communicate with each other as efficiently because the stretching and tearing of the nerve fibers set in motion electrochemical damage to the brain’s wiring system. Damage due to stretching, twisting, and tearing is more common when there is a rotational component to the forces applied to the brain.

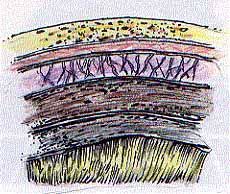

What the Brain Looks Like Before Diffuse Axonal Injury

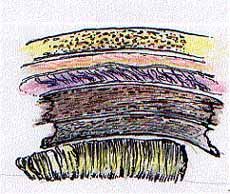

The brain is made up of different layers that have different densities. The neurons run through these different layers. When the head is not moving rapidly, no stress is placed on the neurons and the axons that interconnect the neurons.

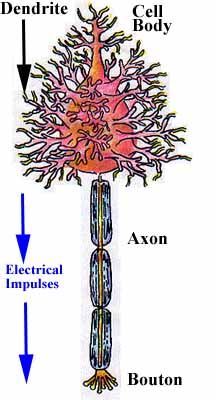

This diagram shows a neuron functioning normally with the electrical impulses flowing from one neuron through the axon and onto the dendrites of the next neuron.

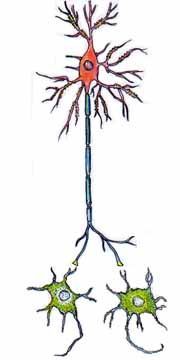

Here you can see how one neuron connects to another neuron. There is a very small gap between the bouton (end of the neuron) and the dendrites of the neuron to which it connects. Electrical impulses travel from the cell body down through the axon until they reach the bouton. The impulses are conveyed chemically from the bouton to the dendrites by substances called neurotransmitters.

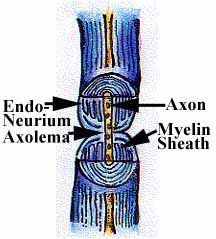

This shows a close-up view of an axon that has not been injured.

What Happens to the Brain When Diffuse Axonal Injury Occurs

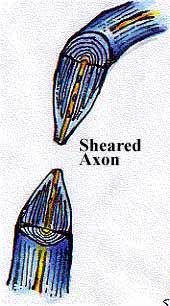

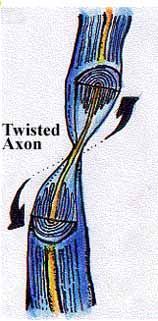

When the head moves, the brain also moves. The different layers of the brain move at different times because each layer has a different density. The illustration shows this movement and how it can result in stress and strain being placed on the neurons and the axons that run though the brain. The axons can end up being stretched, sheared, twisted, or compressed. The next four sketches show a detailed view of what happens to an axon when it is stretched, sheared, twisted, and compressed.

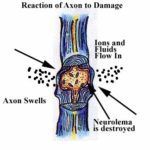

The flow of ions and fluid into the axon causes it to swell, which in turn leads to the destruction of the neurolemma.

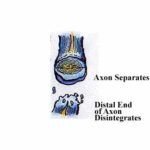

The axon separates in the swelling. The end of the axon that is farthest away from the cell body disintegrates.

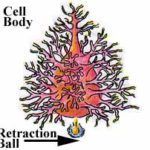

In the final stage of diffuse axonal injury, the distal end of the axon has disintegrated, the remaining portion of the axon has died off, and all that is left is a small retraction ball at the base of the cell body of the neuron.

Contusion from the Brain Hitting the Skull

Contusions or bruising is likely to occur when outside energy causes a portion of the brain to crash into the inner surface of the skull. While contusions can occur anywhere, they are most common in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain.

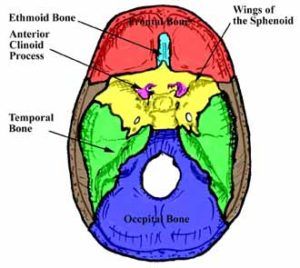

The wings of the sphenoid, temporal bone, ethmoid bone, and anterior clinoid process have very rough edges that line the surface of the lower portion of the skull. This part of the skull cradles the lower tips of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain.

The remaining surface of the skull is relatively smooth. When the frontal and temporal lobes slide over these hard areas, bruising and tearing is common. This mechanism explains why damage to the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain the most common area of traumatic brain injury is.

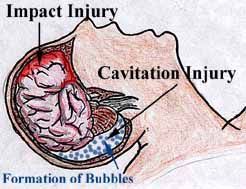

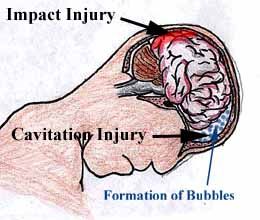

Coup Contre-Coup Injury (Cavitation )

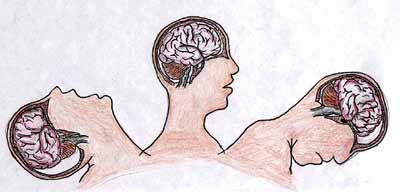

Coup Contre-Coup injuries can happen anytime that a person’s head is suddenly accelerated. The terms “coup” and “contre-coup” are French terms that mean “blow” and “against the blow.” The coup injury is caused by the brain hitting the interior of the skull; the contre-coup injury occurs directly opposite the blow due to a process called cavitation.

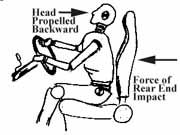

The most common examples of these injuries come from car wrecks. Perhaps the simplest case can occur when you are a passenger in a car that rear ends another vehicle. When your car’s forward motion stops suddenly, your head keeps on moving until it can go no further, and your head comes to a sudden stop. (This is the same process that causes your sack of groceries to crash into the dash when you must stop suddenly.) After your head stops, it is likely that your head will rebound and travel backward. This action may repeat itself several times.

A similar process happens inside the skull. The brain is a passenger inside the skull riding only on a thin layer of cerebral spinal fluid. Just as your head kept on going when the car stopped suddenly, your brain slides backward until it can go no further and suddenly crashes into the back of the skull. A bruising injury occurs to the brain because of the direct impact with the skull.

Now for the cavitation part of the injury. Cavitation is the formation of air bubbles in a liquid at low pressure when the liquid is accelerated. The sudden movement of the head forward sets up the cavitation process. An area of low pressure within the microvascular system (minute blood vessels) at the front of the brain develops. The brain, which initially had struck the rear of the skull, now starts moving forward. The area of low pressure at the front of the brain is suddenly converted into an area of high pressure. The sudden change in pressure within the microvascular system at the front of the brain destroys the air bubbles in the blood. The rapid creation and destruction of these air bubbles damages the microvascular system that feeds oxygen to the front of the brain. The result is brain damage in the area directly opposite the place where the brain first hit the skull.

As the head rebounds backward, the process reverses. The brain slides forward until it crashes into the front of the skull. An area of low pressure is created in the microvascular system at the back of the brain causing bubbles to form in the blood vessels at the back of the brain. When these bubbles collapse as the brain starts moving backward again, damage is done to these blood vessels.

Rear-End Impact

When the head moves, the brain also moves. The different layers of the brain move at different times because each layer has a different density. The illustration shows this movement and how it can result in stress and strain being placed on the neurons and the axons that run though the brain. The axons can end up being stretched, sheared, twisted, or compressed. The next four sketches show a detailed view of what happens to an axon when it is stretched, sheared, twisted, and compressed.

Backward Motion of the Head

When the head moves, the brain also moves. The different layers of the brain move at different times because each layer has a different density. The illustration shows this movement and how it can result in stress and strain being placed on the neurons and the axons that run though the brain. The axons can end up being stretched, sheared, twisted, or compressed. The next four sketches show a detailed view of what happens to an axon when it is stretched, sheared, twisted, and compressed.

Forward Motion of the Head

When the head moves, the brain also moves. The different layers of the brain move at different times because each layer has a different density. The illustration shows this movement and how it can result in stress and strain being placed on the neurons and the axons that run though the brain. The axons can end up being stretched, sheared, twisted, or compressed. The next four sketches show a detailed view of what happens to an axon when it is stretched, sheared, twisted, and compressed.

Excito-Toxicity

When an axon is stretched and damaged, the brain responds by releasing many neurotransmitters. The neurotransmitters in turn may cause chemical damage to the brain.

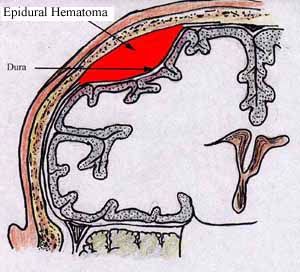

Hematomas

A rupture of a blood vessel inside the head may lead to heavy bleeding or slow leakage of blood out of a blood vessel. The blood will tend to accumulate inside the head and form a hematoma.

An

epidural hematoma forms between the skull and the dura mater, the tough outer membrane that covers the brain. Epidural hematomas are most seen in conjunction with a skull fracture. If the hematoma is not removed, it can cause brain damage by putting pressure on the brain.

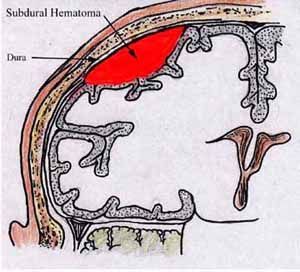

A

subdural hematoma forms between the dura mater and the underlying membranes that cover the brain. These hematomas are seen most often in association with direct damage to the brain. Symptoms from hematomas may appear immediately or gradually as blood seeps out of torn blood vessels.

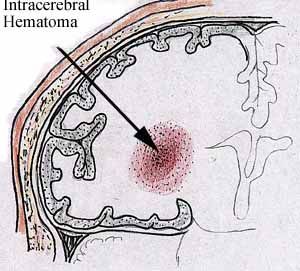

Intracerebral hematomas result from accumulation of blood within the brain caused by bleeding in and around the brain.

Call our office today at (402) 393-1435 to request a consultation.